Paul Procter

Paul Procter is one of the most respected and accomplished dry-fly anglers in the world. Renowned for his technical precision, refined presentation, and deep understanding of trout behaviour, Paul has devoted his angling life to pursuing large wild brown trout using floating flies. His work blends traditional dry-fly ethos with modern thinking, making him a leading voice in contemporary fly fishing. Paul now works as a consultant and product developer at Guideline Flyfishing.

1. Choice of equipment Rods, reels, fly lines, fly floatants, clothes, glasses and other useful items.

I believe in slightly longer rods these days with a medium action. Granted a 9-footer is much easier to turn through the air in blustery conditions, however the reach of a more lofty outfit wins hands down in terms of line manipulation and mending, which is a vital element of dry fly fishing. The Guideline LPX Tactical 9’9” models are an excellent compromise as they remain ‘zippy’ in breezy weather and yet they manage line perfectly. For spring fishing I’ll lean towards a 4-weight rated 9’9” Guideline Tactical as this possesses the required guts to cope with niggling headwinds and of course the throes of boisterous trout. Yet, there’s the necessary finesse where trout seem edgy.

All that said, when it comes to low, clear water and/or bright conditions, I’ll step down to the Guideline Tactical 9’9” 3-weight, in fact, this is fast becoming my ‘go to’ rod. It’s just has a wonderful delicate feel and delivery about it that still has surprising reserve in the butt section to bully large trout away from structure. What’s more, you feel super confident using flimsy tippets when more diminutive flies are the order of the day. I’m super paranoid about “flash” on all equipment, right down to my snips, which is why I select rods with a matt finish and non reflective rod rings. Furthermore the Guideline Tactical series have an un-ground blank, which I personally find quite attractive .

Fly lines

These days weight forward (WF) fly lines are refined so they land like thistledown, which is why I prefer them. My reasoning is simple, many of our casts when dry fly fishing on rivers rarely extend beyond 50ft and often far less. A simple equation here; let’s assume we are casting at a trout 50ft away using a 15ft leader. Deducting the 15ft leader and damn near 10ft of line still within the rod rings means we only aerialise 25ft of fly line. Even when using a short head WF line the head (belly) section is still likely to be in the rod’s tip ring, which ultimately means our fly line is extremely stable during false casts, just like a double taper. Furthermore, where restricted room hampers our back casts we have to rely on shooting a little more line on the final delivery, which is easily achieved using a WF line. Finally, coping with blustery headwinds is much easier using a short head WF line.

I prefer more supple fly lines that are easy to gather up in limp coils when retrieving them. Granted, you might argue they posses more line sag between rods rings that affects line shooting capabilities, yet we’re not reaching for the horizon here. Bear in mind too, biblical fly hatches often occur on chilly, damp days when frigid temperatures can make your fly line feel stiffer, so an already wiry fly line becomes a hindrance now.

Fly line colour is always going to be a contentious issue. I’m more you’re understated sort, who leans towards olive or grey lines. That said, there’s an argument that all fly lines at rest on the water’s surface cast the same colour shadow, that of a dark one! What’s more, when viewed from beneath, fly lines all appear as a dark outline. The only argument I’ve have is a garish fly line moving backwards and forwards during false casting under a gantry of trees might just catch the eye of a fish!

Admittedly there’s an exhaustive number of WF profiles out there these days and trying to select the best one to suit your needs can be bewildering, especially for beginners. For me, a good all-rounder is the Guideline Presentation Plus. It has a good, honest taper that really does deliver under all circumstances. What’s more there’s enough ‘oomph’ there when it comes to flinging large, bushy dry fly creations, like mayflies for example.

Reels

When it comes to reels, I prefer a disc drag model though this is purely for longevity in my eyes and not for stopping power. As let’s be honest, most trout slog it out in their immediate domain, especially gnarly, old brown trout that insist on getting under tree roots, boulders and sunken logs rather than sprinting for the horizon. One thing I look for on a reel is a subdued finish like the Guideline Fario #2/4 Dk Green/Grey model.

As mentioned, all my gadgets and fishing paraphernalia have a dull, sombre finish that’s not reflective. Like rod, reel and line here, the idea is to prevent any flash, or glint, which in turn could warn a trout all is not well. I appreciate it sounds paranoid, but think how many times your attention is grabbed by the flash of another angler’s rod, reel, our silver forceps hanging from their vest.

For the same reason, I select clothing that blends in with olives, browns and tans forming my fishing wardrobe. By the

same token, I’ve never felt the need to be completely decked out in camo gear, which is perhaps a step too far for me.

The main thing is to blend in and move slowly with purpose rather than dash along the banks in a rush to get to the next perceived honey hole!

Decent polariods are a must in my book. I tend avoid the mirror finish types that seem all the rage amongst the saltwater fraternity, as whilst all lenses reflect light those with a mirror finish are the worst culprits. Polariods with amber lenses are my choice as not are they a decent all-rounder, they enhance light on cloudy days, or during the more obscure light of dawn and dusk. An absolute blessing are the Amber Guideline Ambush specs which have a 3x magnification window at the bottom of the lens, which makes changing flies a dream. For revamping sodden dry flies a hand towel that costs 50p

A hand towel is ideal for revamping sodden dry flies has never let me down.

If CDC patterns are being used they are given a wee bit more care in the form of dry fly powder. I prefer to use a brush here to massage right into the root of CdC wings

High N Dry Dry fly powder should be massaged right into the root of any CdC wing.

2. Leader material, build up, length and knots.

I’ve never been one for complex leader recipes that require tape measures and micrometers as whilst these are straightforward to construct at home they’re a devil to replicate on the river bank when a brutal downstream wind buffets you!

For the sake of sounding agricultural, in essence then, an 8ft tapered section is cropped from the Guideline Power Strike Pro leader forms my datum. Using perfection loops (or a tippet ring on the thinner tipper end), to this I add lengths of monofilament in various diameters. I’m not too precious about exact measurements either, as leaders are touchy-feely affairs that need casting first on a given day to see how they perform. After all, turning over 20ft of flimsy leader in the teeth of a howling gale isn’t a walk in the park and something beyond most folk, including myself, so why make it difficult?

A reasonable starting point would be a GL 12ft 3X Dry & Stealth Light taper that with approx 3.5ft cropped from the butt end. Six inches or so will be used up when forming knots to result in an 8ft taper overall that concludes in approx 0.20mm. A simple formula would include attaching 3ft of 0.185mm dia (4X) Pro Strike copolymer and a 5ft of 0.152mm (5X) to result in a 16ft leader overall. You’ll notice the tippet seems long and the idea being this will hinge or flail a little to provide required slack, thus allowing your fly that little extra freedom to drift unfettered.

Of course diameters might vary as will lengths to suit situations. An example; the leader might be shortened by removing say 1ft of 4X and 2 ft of 5X, resulting in an overall leader of 13ft to say cope with blustery weather.

For me, longer leaders are beneficial given low, clear water, or when using smaller imitations. They’re also handy where complex currents exist, like pocket water for example. Shorter leaders might be called for when a breeze gets up, or when you’re in a tight stops as they’re easier to turn over with short, snappy casts.

Finally, a word on tippet diameters, which are a trade off with regards to improved presentation versus strength. Obviously, finer connections allow our imitations to move freely and appear convincing though might not be up to dealing with headstrong fish. Sturdy tippets however help you horse trout away from danger, yet being thicker they shackle flies to a point causing unwanted drag.

0.15mm tippets might seem alarmingly thick to many. However, much of my dry fly fishing revolves around larger trout on freestone rivers, littered in snags. Naturally the heavier your tippet the more it shackles your imitation, making it appear unnatural though it’s surprising what you can get away with. Admittedly, I do go finer, but only following a refusal or two and even then, rarely drop below 0.13mm.

3. Approach and stealth.

For me, one of the most important aspects of fly fishing is your initial approach. After all, if fish are spooked prior to unlatching the fly, you aren’t going to fool trout no matter how sophisticated, or expensive your terminal tackle is.

Both prey and predator, wild trout are highly tuned creatures that constantly monitor their surroundings for subtle changes, which might alert them to possible danger. It goes without saying then our approach should be both silent and unobtrusive.

To remain quiet my wading boots never have studs in their soles as these crunching under foot could potentially warn fish, especially in drought conditions where little “white noise” exists due to lack of flows. Given this, your footfalls ideally need to be delicate, pretty much like a leopard stalking its prey, as dislodging bank side stones and the likes as you creep up on a feeding fish is never going to end in your favour! To that end, wading staffs are given a wide berth by me too, due to seeing so many clients wrestling with these clattering appendages when attempting to advance of rising fish.

When approaching trout I habitually try to make myself as small as possible. Typically this involves crouching, or edging forwards on hands and knees. For the sake of my knees and preventing wader punctures a pair of knee/shin pads now rank high on my tackle list.

Knee pads have become an essential tackle item for me.

4. Reading the water.

The ability to read water when fly fishing ought to become second nature. That said, mapping out a river in your mind’s eye is an ever developing skill. Naturally, we’re bound to rely on past experience to point us in the right direction. Yet, each time we visit a beat, it’s unique due to prevailing conditions.

I’m fortunate to fish more than most folk, so have quite a relaxed approach these days. Rather than dash in and start casting, I’m content to sit back and study a pool for several minutes. Naturally, my first scan of a pool is for rise forms, or any signs of life fly that might encourage fish to stir.

I tend to break a section of water up on a priority basis, focussing most where I’d expect to see a fish move, or the places trout are most likely to lie. These include foam lanes (bubble lines), creases and seams caused by protruding boulders, or bankside obstructions and back eddies. My eyes are always searching out the demarcation lines between hard (broken) and soft (flat) water that indicates a sudden change in depth by way of a ledge. Such places attract trout like bees to honey as they have the curtain of shallow, popply water to feed under with deep, inky depths nearby as an escape route when danger threatens.

Something else, I’ll often watch a pool from both banks as light angles give a totally different perspective on the nature of water when you’ll often identify a feature that wasn’t obvious from the opposite bank!

5. Casting ability and which casts are essential.

In many respects, casting is a means to an end, in that you don’t need to be highly tuned casting instructor to catch fish. We often find ourselves in many awkward situations when hunting wild trout using dry flies. These circumstances generally call for more unorthodox casts and manoeuvres in order to get a fly in front of a fish.

However, for the sake of sounding like a hypocrite, a better understanding and execution of a cast increases our odds of success tenfold. Those who fish pressured waters in places like New Zealand will hopefully be nodding knowingly now by way of the mantra “make that first cast count”! Admittedly, it’s a generalisation, but the more casts you end up making at a given fish the more likelihood you’ll be clocked by your quarry. Furthermore, a smooth and slick style equates to less false casts when covering rise forms. Again, fewer movements reduce the chances of trout cottoning on.

Distance is rarely a necessity when river trouting as we usually close the gap on fish so my focus lies in presentation casts. Naturally, many casts are merely derived from the overhead cast. Some sort of slack line ought to be in your armoury. For introducing reasonable amounts of slack, my favourite is the bounce cast.

The reason I prefer this is because it’s dynamic as opposed to other slack line deliveries that are more passive by nature. This means, even in breezy conditions the bounce cast has sufficient impetus to land on target. Yet other slack line presentations are easily blown off course due to wider loops and more relaxed casting stroke.

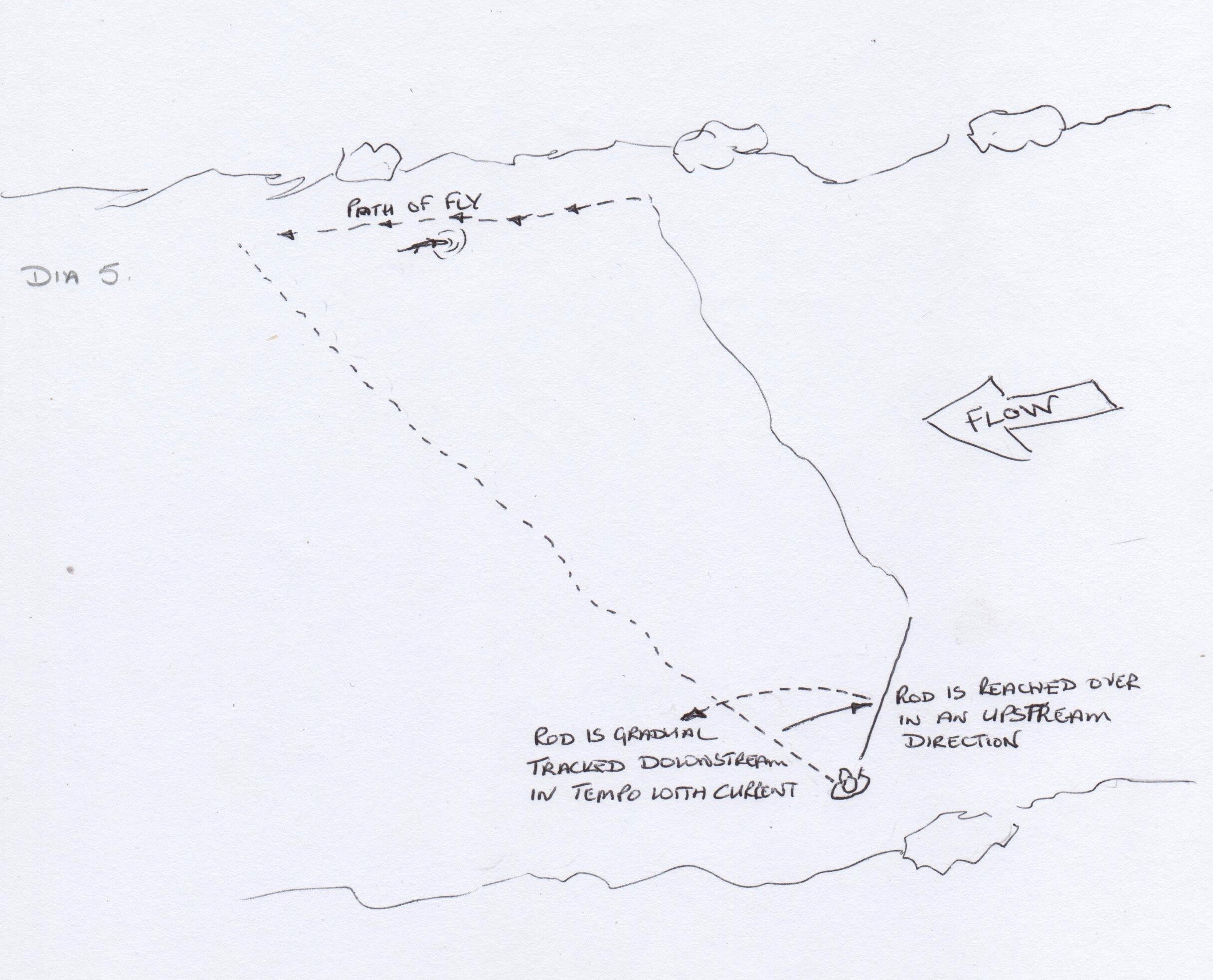

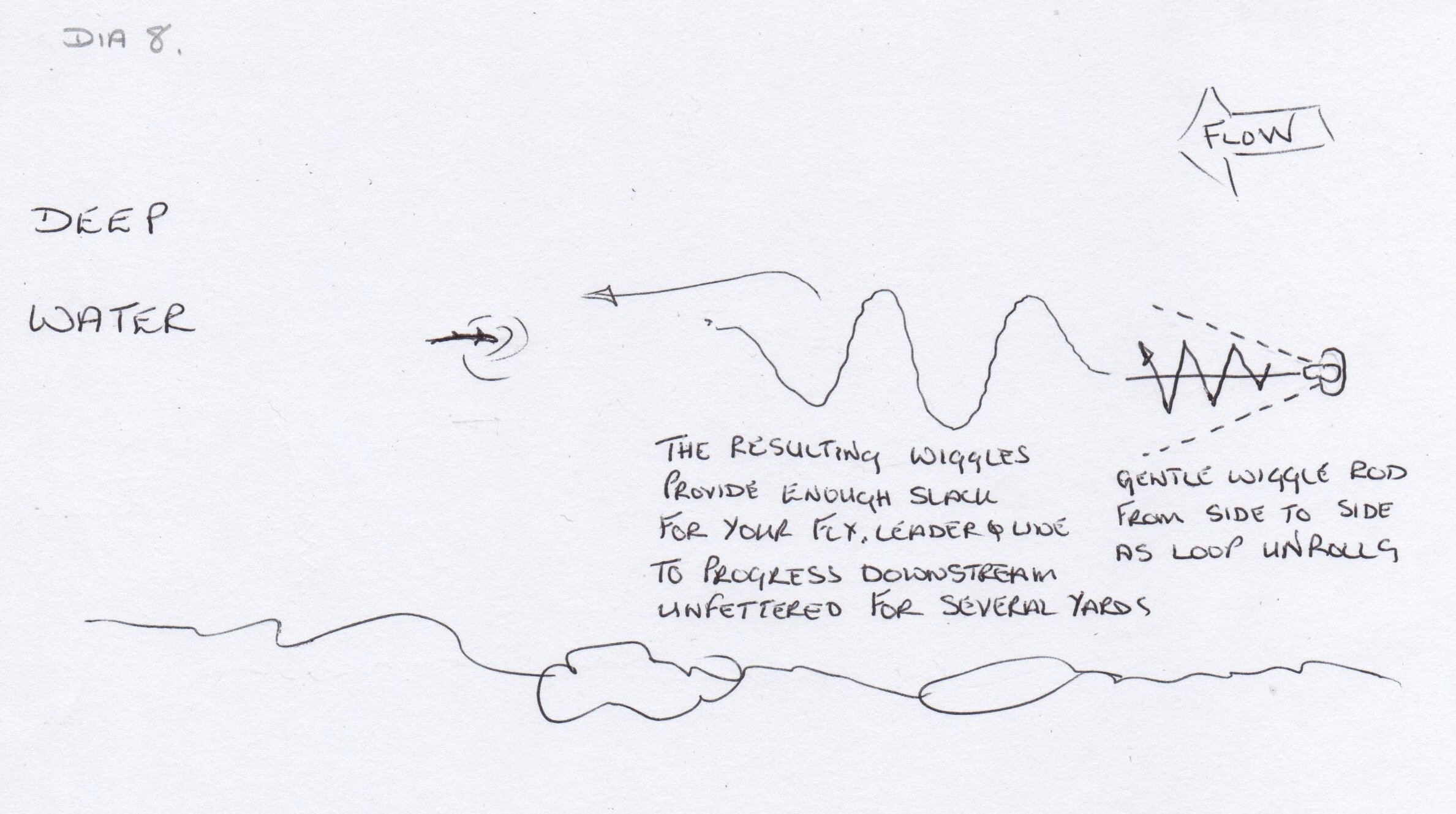

Another essential is the reach cast that lays off your fly line (usually in an upstream direction) to one side, or another when pitching at fish opposite to you. Not only does this facilitate longer, drag free drifts by tracking your line with the rod in tempo with currents Dia 5, but it prevents leader, and or fly line from landing over a trout’s head when you’re throwing at fish upstream of you Dia 6.

6. Entomology, what should we know.

I put a huge emphasis on the understanding of bugs. It’s not so much to impress others with Latin names and the likes, but to have an understanding of what is occurring and what might happen on your stream any time soon. On a personal basis, this has been taken to another level by me, purely because of my interests in trout food and of course, conservation in an ever deteriorating environment.

Basic Entomology need be no more than recognising trout are taking a particular fly at a specific stage. Hell, you don’t even have to identify them, after all, as far as fish are concerned, it’s might be a wee olive jobbie that’s easily intercepted at the surface. Simply put then “Entomology” can be dressed up as observation. To that end, make a point of checking cobwebs in hedgerows, gateways an on any bridges (see photo below) during your short stroll to the river as these provide clues before to help us make an informed choice of fly once we reach the water’s edge.

Spider’s webs provide vital clues, upwing (olive) spinners are likely to be on the menu.

7. Rise Forms; Can they tell us something?

Rise forms tell us an awful lot. Firstly, they help determine the general size of a trout. Contrary to belief, as many seasoned anglers know, larger trout often rise with little fuss. You see, if a sizeable trout responds quickly to intercept a morsel their sheer mass moves more water, which can cause their intended target at the surface to be knocked off its path of travel a nano second before a trout aims to eat it. The outcome is a fish misses the food item, wasting precious energy into the bargain.

Studying a feeding fish for several minutes also provides us with clues as to what they might be eating. Imagine it’s early season and the only fly hatching are large dark olives. You watch a procession of duns filtered over the head of a fish that leaves them unmolested, yet is seen rising. By elimination, it is odds on this trout is nabbing emerging nymphs, invisible to our eye.

We’re often guilty of assuming fish religiously rise in the same spot time and again. Yet, many times they will traverse the current picking off flies. This is especially the case during sparse hatches, or falls of fly. Here, we can determine how far a fish might swing to secure a meal. Such useful information translates as not having to land your fly directly upstream of a fish, but maybe to one side by a couple of feet.

The regularity of a rise provides us with pointers when approaching a fish. Trout feeding like the proverbial metronome are so busy feeding their guard is down a little more than usual, allowing us to get that bit nearer. More infrequent risers however are generally on high alert much of the time. Now, we have to be at the top of our games if we’re to succeed!

8. Fly selection, Size, shape, materials, which flies are essential.

Dry fly fishing involves copying naturals, so it makes sense that our imitations are of a similar size, shape and colour. That said, during blanket hatches, our offering can be lost amidst a sea of naturals. It makes sense now to make our fly stand out by increasing its size. Colour too can be influential when the inclusion of more lurid shades makes our fly more obvious, especially during low light, or when water is turbid.

PP Pearly Butt

Conversely there might be times when smaller artificials hold sway. Fish that take our fly and have been missed, or those that snub flies can be a sucker for a smaller, imitation. To some degree more diminutive dressings work best on flat, smooth water whereas larger, scruffy effigies should be reserved for fast tumbling water, or where we rely on searching methods to pull trout up.

PP APT

PP All Foam Beetle

PP Stuck Shuck Dun

9. Presentation and drifts.

Granted, casting is often parcelled up as “presentation”, however, simply put, presentation is showing a fish a fly that behaves in a convincing manner and where it expects to see it! I was brought up on a diet of drag free drifts, so your fly conforms to surrounding currents. On the whole this is very much the case, however there are times when a “worked” fly is more appealing.

Some years ago during a decent mayfly hatch on a wee Irish stream, trout ignored a studiously drifted fly. Having covered another fish without so much as a sniff, I began gathering up line to recast when a trout pounced on the fly. The penny dropped as watching rise forms after this encounter revealed fish singling out duns fluttering, or wobbled at the surface. From here on in, as my fly neared a fish a gently shake of the rod tip was enough to shudder my fly and attract trout.

The same can be said where more lively insects occur, like caddis fly for example. Immediately after emerging, in a bid to get airborne, winged adults often hop and skip across the surface. Naturally this doesn’t go unnoticed by trout when a fly that periodically skates across water out-fishes a static pattern.

11. Fighting fish.

Each fish we hook are unique in every single way, so fighting them is somewhat subjective. That said there are pointers to help us gain the upper hand. I’m very much for taking the fight to a fish rather than letting them have free rein. Where possible try keeping trout on a short leash as applying pressure and turning them is then more direct.

Of course, when initially hooked and therefore fresh, most trout make a mad dash. Rather than remaining static, I follow them whilst reeling in line. A vertical rod at this stage holds line out of the water reducing pressure and preventing any sunken fly line from being wrapped around snags by belligerent trout.

Once that first electrifying run is over, I close in and apply side strain by angling my rod in a horizontal plane. This really does exert more pressure on trout and ultimately helps you steer them away from danger. For example, a fish bolting to the left should be countered by you swinging the rod to your right and vice versa.

This action often causes trout to twist, then turn and such energy expenditure will tire them sooner. As they become more disorientated now, fish are netted far more quickly than if you leave them to tow you around a pool.

Netting fish, especially prize ones, is perhaps the most crucial stage. With hardly any line outside the rod tip there is barely any stretch in our system. Now, a vertical rod results in only the tip coming into play thereby reducing unnecessary pressure and guarding against any last-minute violent head shakes from a disgruntled fish. Finally, where possible guide fish into the net headfirst as the trout’s body will always follow it head and, of course conveniently for us, fish don’t have a reverse gear!