Peter Hayes and Don Stazicker

Dry Fly fishing is almost never dry.

Photo: Richard Faulks Trout and Salmon Magazine

Photos by Don Stazicker

The Floating Fly is what we all love to use, however “one major conclusion from our four years of photo and video research is that dry fly fishing is almost never dry”.

The natural is dry, the artificial not.

When we are looking at and recording the dry fly, defined as an artificial fly that is perfectly dry and sits on the surface and completely above it, our long series of experiments showed conclusively that this just does not happen. All flies penetrate the surface when cast in normal ways and environments, however good the caster and however skilled the tyer. Because of that they are, paradoxically, preferentially taken by trout because the trout identify them as less likely to escape, and therefore vulnerable, and therefore providing more nourishment for less energy spend, and less risk of energy waste. Therefore the success of "dry fly fishing" in catching trout is actually reinforced by our failure to fish the fly as we intended…dry: floating, yes, dry no. Vulnerability successfully suggested every time.

Over the last century and a half, millions of hours have been spent by fly-tiers trying to make artificials look as if they are about to fly away—precisely the opposite of what the trout is looking for. Instead, the key to successful fly design, and to presentation, is to suggest vulnerability.

Consequently and in a related logic, there is a clear tendency evident from our filming for trout not to divert too far from their central feeding line to intercept fully hatched duns. This is in contrast to their willingness to travel several feet to a nymph or to a fly identifiable by its prey image as having a failed to emerge or become trapped.

The last word on the perfect dry fly to imitate the dun is, that it is broadly speaking unachievable within the presentation skills of the normal fly fisher. It cannot, in practical terms, be sustainably presented on, rather than in the surface, above the trout’s mirror, because it will penetrate the film… and even if you could achieve that, you could be doing something else more likely to be effective because it better suggests vulnerability.

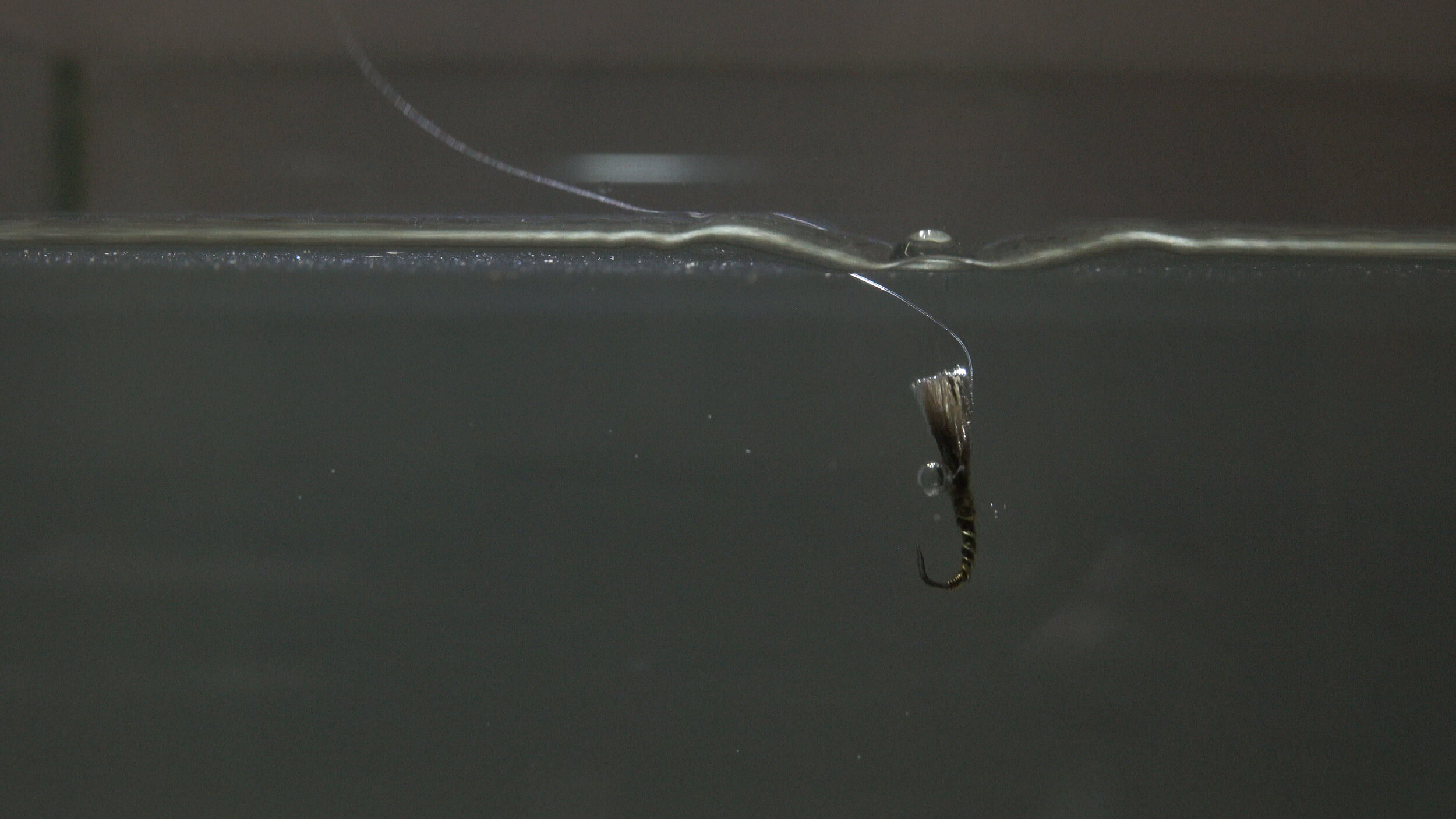

Only if you have stood with cameras beside the landing zone and had your friend cast his perfect fly hundreds of times as perfectly as he can, do you get to understand how far short of perfection we fall. Most of the time the fly lands with some kind of a splash that mashes it into the surface. Even when it does not splash down, its weight, which is 3 to 4 times that of the natural, presses any bits of it that stick out, down through the surface. The hook is going to stick through the surface, whatever your partner does, unless his pattern is one of those upside-down duns which we find mainly don't work.

So, effectively, the trout is never going to see an artificial that is only a set of foot-speckles, and will always see something sticking down through the surface

As mentioned above, trout that are on the fin and feeding on nymphs, emergers, failed hatchers and casualty duns will, our videos show, travel many feet to take a nymph, quite a way to take a failed hatcher, that is trapped with identifying bits visible in or below the mirror: but not very far at all to take a hatched dun. This is for two good reasons. Firstly, the trout will have wasted energy swimming over to inspect many such things in its life so far, only to have them fly away. Secondly, if it is floating past on the mirror and outside the trout’s window, any distance to the right or left of it, the fish will very likely not be able to pick it out because of its the narrow angle of vision from high in the water and intervening bubbles and flotsam. Under water video shows this clearly. It will not identify itself as fitting a prey image by coming into the window for inspection, unless the fish expends energy taking its window to the possible prey for a better view.

So, if you have a perfect dun to offer the trout, you had better cast it with supreme accuracy: for all practical purposes, within a corridor about as many inches either side of the fish, as the fish is deep. It needs to drift down within the diameter of the trout’s window.

Make no mistake, we are not saying that trout do not eat duns, of course they do. They just do not necessarily eat them preferentially or go out of their way to intercept them. If they come pretty much straight down the food lane and appear at the forward edge of the Plain Sight Zone of the window no fish is going to fail to eat them. Sure, trout will eat the hatched dun if they don't have to swim too far for it, and they will eat your artificial one too as the real thing, if it gets cast close enough to their feeding line and it floats high enough. But mostly it won’t, and they won’t.

Our approach to fishing with floating flies in and on the surface is a non-binary approach: not perfectly dry (unachievable) and not fully wet (undesirable)—in a word, suggesting maximum vulnerability. And we want where possible to make the fly sit in the film and move in a way that the most common prey items move, so as to get the trout’s attention and demand a rise. Several new fly designs have resulted, of which the class leader is:-

Pop Up Emerger: The close turns of wire at the bend of the hook are crucial to the correct behaviour of this fly.

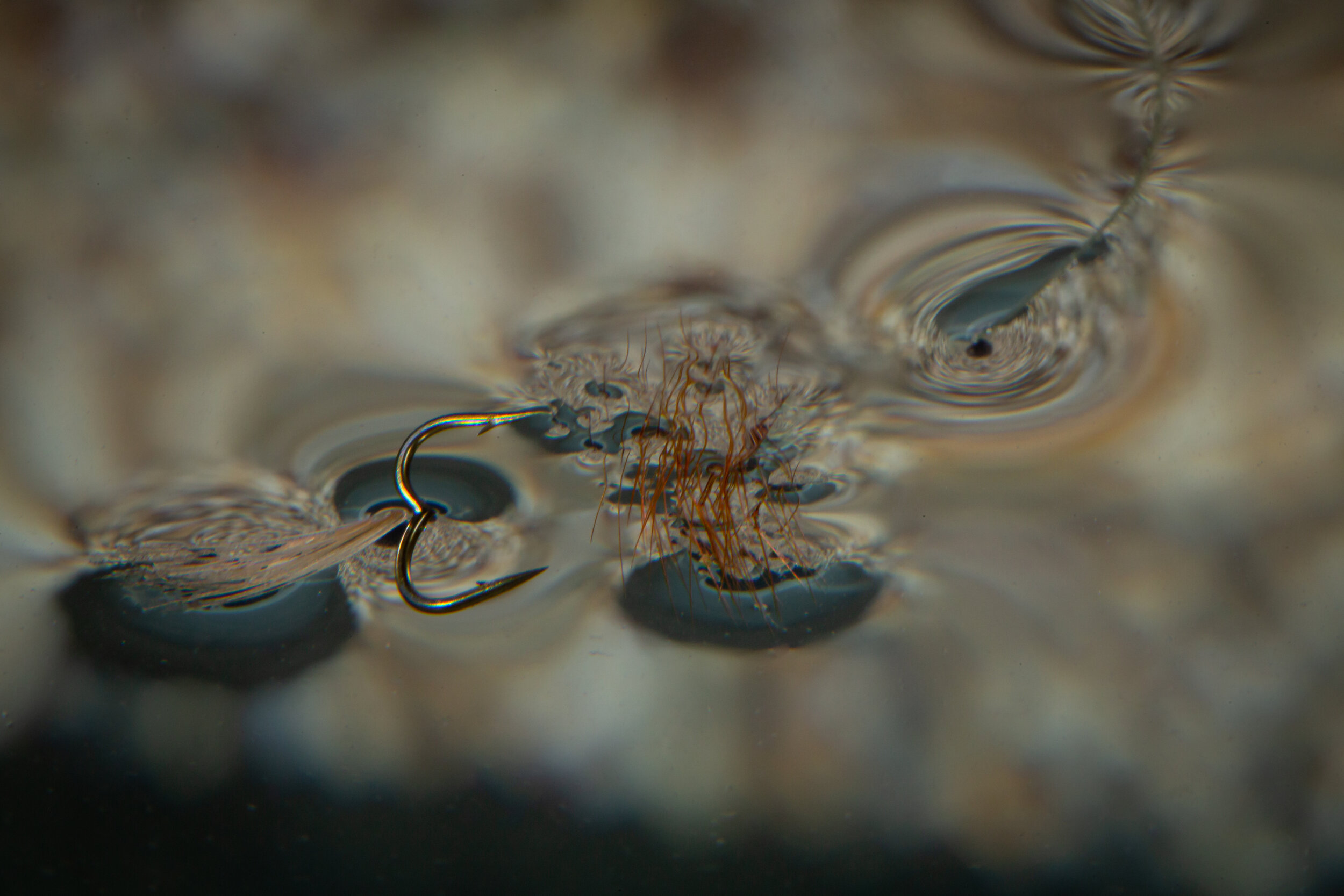

This pattern has been extremely successful in hatches of upwings in the UK and on the spring creeks of New Zealand and Montana. What is amazing about it is that, if cast in a way that allows it to drop from a height, or in close quarters with a tuck cast, it penetrates the surface and sinks to an inch or two – but then pops back up through the surface and sits there, held by the CDC wing. This really gets the trout's attention. Basically, we think it succeeds at least partially in representing the one thing that it is hard for the angler to achieve – a nymph rising up and ecloding through the surface. The cherry on the cake came when we filmed this fly from under water. We saw, every time it was cast the right way, as it penetrated the surface a flash of light from the silver coating of air surrounding the CDC wing. That flash popped back up to, and through the surface, leaving the fly, sitting in the film with the abdomen sub-surface and the wing supporting it clearly visible above the surface. In practice, it works a treat: it gets the trout's attention; it performs an action that the trout is looking for; and then looks for all purposes like a delayed or failing emerger as it comes down into the window, its CDC wing appearing over the edge of the window as normal. There was only one possible name for it: the "Pop Up Emerger".

Pop Up Emerger: the air surrounding the CDC wing gives off a fish-attracting flash before the fly floats back to the surface and “emerges” as the wing penetrates the surface and fans out.

This 20” brown was an early success for the Pop Up Emerger.

We have also designed the “Pop Up Midge” and the “Film Clinger Nymph” to float, and hang without sinking, but be explicitly vulnerable in the non-binary environment.

“Film Clinger Nymph”working on the river “.

For the more traditionally inclined dry fly angler we have produced a core, variable recipe for a “dry” fly designed to imitate the most vulnerable forms that the adult fly presents in. If (or rather when) it penetrates the surface it will be a good thing, and if it gets crumpled and scruffy it will work all the better.

When we have filmed trout eating casualty duns we have not seen them become selective to any particular form. As a result we have found that a "messed up" representation of a recognisable adult fly that has become compromised will secure the attention of a fish. We think that trout can become selective in general terms to casualty duns, but non-selective as to the precise form in which they present. Enough of a suggestion of a familiar edible item will have to be present (or it will not be recognised as edible and nutritious) but the messed-up overall appearance of it will add vulnerability and get it targeted.

We think there must be an essential “sine qua non”, a central component suggesting nourishment – one that is a familiar component of prey items currently in the larder. We think that that is almost certainly the abdomen, with its typical semi-translucency, in the same colour as a dun that is hatching. The abdomen/thorax is the one part of the dun that very rarely gets trashed: it is the one consistent component. It provides the most nourishment, and there is probably an oral, tongue-to-roof-of-mouth recognition factor that gives rise to operant conditioning and reinforces the generalised selectivity to these casualty duns in spite of their lack of a consistent appearance.

Probably that abdomen is curved, and curved in the direction of the wings, up towards the dorsum, the back of the fly.

Messy, scruffy, imperfect wings provide the necessary suggestion that this fly has had an accident and is vulnerable. All of which leads us to a fly to imitate casualty duns with a curved-up abdomen and wings of Zing-Wing, Zelon, CDC, or organza. This format has worked very well indeed for us in the imitation of post-laying casualty stoneflies as well as upwing duns and spinners.

Following a pattern with precision is not necessary. It is only flytying zealotry that says you have to tie each fly precisely to a pattern and exactly like the last one: a hidden assumptive law that we think inhibits imitative progress. We think it is more useful to tie surface flies with intentional diversity, to match the accidental diversity of the casualties.

Our name for this catch-all casualty: the “Not The Dun Thing”. This can be either: 1) A dun tied with its wings at a 45-60° angle to each other, and strong tails, to fall over and rest with one wing in the film. Wing of natural CDC or light grey feather fibre; or 2) A casualty dun tied to lie with both wings in the film. Wings tied spent spinner style of CDC, Zelon or a synthetic film wing material such as Zing Wing or Medallion Sheeting and a tail of soft feather fibres such as mallard flank, Zelon or a combination of both materials. Many other recipes are possible.

A photo of one common format for a casualty dun, and its imitation, follow at the end of this article.

“click here to watch a big trout feeding on casualty duns this on Nelson’s spring creek in Montana”.

Don and I hope we have convinced you that we are neither Dry Fly Fishers, nor Authorities!

Zing Wing casualty dun

Drowned casualty dun

Five years ago, I decided to revisit the technical thoughts about how trout and flies interact that I had addressed in my first book "Fly Fishing Outside the Box, Emerging Heresies" – the objective being to muster much better evidence and test its conclusions as well as opening new lines of enquiry. I recruited my friend Don Stazicker, whose videographic skills are legendary, as my co-author. We used newly-affordable high end video and still cameras (producing 4K video and the ability to freeze up to 250 frames a second). Don and I researched and experimented over four seasons and finally published our e-book "Trout and Flies, Getting Closer" at the end of last year. We set out to investigate as far as possible what really happens when trout take flies, both natural and artificial. The results sometimes supported what we thought we knew but often they overturned our comfortable assumptions.

There are many theories in fly fishing and often that's just what they are, theories. We've been there and bought the books, some that just repeat the ideas of previous authors and some that contain original research. But many theories and ideas prevalent amongst those who fly fish for trout have no basis in fact or are just dead wrong.

How have we been able to see better what is happening when trout feed?

We have used high definition slow motion video to analyse the behaviour of fish, the prey on which they feed and the imitations and methods of presentation used to catch them. By slowing down the action, we have been able to see what escapes the unaided human eye. We have filmed trout feeding on the surface and underwater and the results have fundamentally altered how we tie and present our flies, especially to selective, hard to catch fish.

Over four years of fishing and filming on rivers around the world have been distilled into this book making it invaluable for fly fishers, from beginners to experts, fishing on any trout stream from gentle spring creeks to big brawling freestone rivers.

Throughout the book, we use QR codes and hyperlinks to free video clips of our original research. You won't just be reading what we have discovered but you'll be able to look at the video evidence and find out for yourself exactly what you've been missing streamside.

There are new fly patterns designed not only to imitate the appearance of the trout's food but, equally important, its behaviour.

350 high resolution photographs and diagrams make it clear how trout and flies interact.

Knowing more about why your fly fooled the trout lets you own more of the take.

We ask and answer 42 questions of major importance to fly fishing success, such as:

Is any feeding trout uncatchable?

Is presentation more important than imitation?

Are trout ever selective?

When is the rise to a floating fly triggered?

Do trout hold the fly in the window's edge for a better view?

Where is the fly when the trout accepts or rejects it?

How far will trout divert for a dun or a nymph?

Do emerger patterns imitate emergers?

Can we imitate fly behaviour?

Can the rise form tell us the species of fly taken?

“Is reading this book going to change your fly fishing view- as it is has with me? Unequivocally.

Just read and watch.....and learn.

A book of our time....and the future. Trout...be afraid...very afraid”.

Charles Jardine.

“What an extraordinary gift Peter Hayes and Don Stazicker have given us with

Trout and Flies – Getting Closer.

As the song says, You ain’t never seen nothin’ like this before.”

Paul Schullery.

Ah, I nearly forgot the 11 questions!

1. Choice of equipment: Rods, reels, fly lines, fly floatants, clothes, glasses and other useful items?

Rods; 3Wt-5Wt, 6’10”-9’, Orvis Helios 3F, Sage TXL, Hardy Zenith Sintrix. There are some brilliant less expensive rods, but a very few of the latest high end rods will put the fly where your eyes put it every time. Must be non-flash.

Reels; Orvis Mirage, Lamson various. Must be non-flash.

Fly lines; Airflo Dry Fly Elite, Rio Gold. The loop must not unroll flashily towards the fish, so dark in colour.

Fly floatants; Loon Lochsa, Dry powders.

Clothes: Dark, Camo.

Glasses: the best polaroids.

2. Leader material, build up, length and knots? 8’ Polyleader light trout, plus minimum 7’ Trouthunter Fluoro tippet, usually 5X. Longer stronger tippet rather than thinner and shorter.

3. Approach and stealth?

As close as possible. Avoid noise, wave-pushing, and skylining.

4. Reading the water.

We treat extensively of this aspect in “Trout and Flies, Getting Closer”.

5. Casting ability; which casts are essential?

Dump, Side, Bounce-back, and Tuck (we find it hard to deploy the Reach without causing drag to set in early through exerting a straightening pull on the leader).

6. Entomology, what should we know?

How species behave. Which species do trout get selective to, in response to that differentiating behaviour. How do different species most often get to be vulnerable. Terrestrials are a whole diverse subject too!

BWO Casualty dun and shuck

Mayfly Dun trapped in the surface film curved body

Mayfly flat in the surface

Mayfly Dun trapped wing

Casualty Dun

Dun trapped wings in the surface

7. Rise forms: Can they tell us something?

Some simple things, but not as much as earlier writers said - and the human eye can’t see them clearly enough to interpret.

Nelsons spring creek fly pouring into mouth

Brown trout examining an emerging midge

Strike on the Wylye

8. Fly selection, Size, shape, materials, which flies are essential?

Whatever suggests a vulnerable form of what is currently in the fish’s larder.

Para Adams semi- submerged

Film Clinger Nymph

Film Clinger Nymph under water view

Casualty Dun in surface film

Zing Wing casualty viewed from underwater

Traditional dry semi-submerged

Traditional dry semi-submerged underwater

9. Presentation and drifts?

Drag free, and learn about refraction or you will line fish.

10. Upstream or downstream?

Upstream for preference, but whatever it takes to get the fly over the fish accurately and drag-free. We fish a great deal perpendicularly across-stream.

11. Fighting fish?

Keep them upstream, use the middle power bend of the rod, don’t use silly little nets.